The Future of Recycling: Robots, Landfill Mining, and the Economics of Trash

From Separate Bins to Smart Systems

Remember when recycling meant carefully sorting everything into different colored bins—glass in one, aluminum in another, paper in a third, plastics in a fourth? My city used to be like that. Before that, everything just went to "the dump," and we didn't think much about it. Then came the colored tubs, and suddenly we were all amateur waste managers, standing in our kitchens trying to remember which bin gets which bottle. Now? Throw it all in together. The sorting happens automatically after pickup, using systems so sophisticated they can identify and separate materials faster and more accurately than humans ever could. It's amazing progress. But the question that keeps me up at night is: what's next?

The Robot Revolution in Recycling

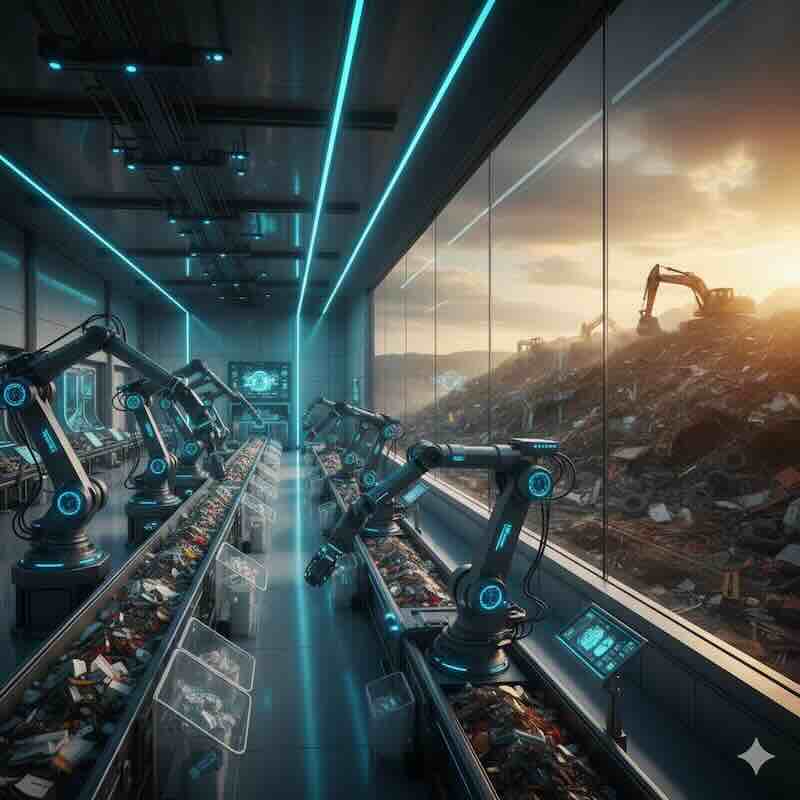

The future of recycling is being reimagined through robots equipped with artificial intelligence and computer vision. Companies like ZenRobotics have developed systems capable of processing up to 70 metric tons of waste per hour, far surpassing what human sorters could achieve. These aren't your grandfather's assembly-line robots—they're sophisticated machines that can recognize materials based on shape, color, texture, and even brand labels, making split-second decisions about where each item should go.

AI-equipped cameras with machine learning algorithms process images in milliseconds, enabling real-time identification of recyclables on fast-moving conveyor belts. The technology continually improves through machine learning, adapting to new packaging materials and changing waste streams. Near-infrared scanners can identify different types of plastics that look identical to the human eye, while robotic arms pluck specific items from mixed waste and place them in appropriate bins with remarkable precision.

The impact goes beyond efficiency. These robots handle hazardous and contaminated materials, creating safer working conditions. They operate 24/7 with consistent accuracy regardless of lighting or fatigue. And here's the kicker: recycling facilities using advanced sorting technologies report increased throughput by 50% while reducing sorting errors by up to 90%. That's not incremental improvement—that's transformation.

Chemical Recycling: Breaking It Down to Build It Back Up

While mechanical recycling physically breaks down plastics, chemical recycling works at the molecular level, turning plastics back into their original building blocks. This means even mixed or contaminated plastics—the stuff that currently ends up in landfills—can be recycled repeatedly without quality degradation. Technologies like pyrolysis, depolymerization, and gasification are making this possible.

The promise here is huge. Chemical recycling could handle the plastics that defeat traditional recycling, like multi-layer food packaging or items contaminated with food residue. But there's a catch: these processes require significant energy inputs and sophisticated facilities. The economics are still being worked out, and the environmental benefits depend heavily on what energy sources power these operations. It's cutting-edge science, but we need to make sure we're not burning more carbon to recycle plastics than we'd save by not making new ones.

The Landfill Question: Mining Yesterday's Trash

Now here's where things get really interesting—and complicated. What about all those massive landfills full of decades of accumulated garbage? Are they going to sit there forever, or will we eventually excavate and recycle that old waste?

The concept is called landfill mining, and it's already happening in some places. The idea is to combine landfill remediation with resource recovery, generating recyclable materials and energy to offset remediation costs. Some projects have been successful—a four-year reclamation project in southern Maine that began in 2011 created an estimated $7.42 million worth of recovered metals. Not bad for digging up old trash.

But here's the brutal economic reality: soil excavation, screening, testing, and deposition can account for 80% of a landfill mining project's cost. Since landfills are mostly soil, those costs add up fast. The cost of excavating trash, sorting valuable materials, and reburying the rest often exceeds revenues from selling recovered materials. In many cases, resource recovery alone can't justify these projects financially—they need additional benefits like land reclamation, pollution prevention, or regulatory compliance to make economic sense.

When Does Green Become Too Expensive?

This is the uncomfortable question nobody wants to ask at cocktail parties: at what point does recycling become economically absurd? When do we hit the wall where the energy, labor, and resources required to recycle something exceed the environmental benefit?

The answer varies wildly depending on the material, location, and specific circumstances. Aluminum recycling is a slam dunk—it uses 95% less energy than producing new aluminum from bauxite. Glass? Less clear-cut, especially if it needs to be transported long distances. Some plastics? Economically questionable depending on contamination levels and market prices for recycled materials.

Landfill mining exemplifies this tension. If projects follow "enhanced landfill mining" principles targeting higher value outputs, the economic balance can become positive, especially for larger landfills where economies of scale matter. But smaller landfills or those with less valuable materials might never pencil out economically, even with the best technology.

The reality is that some recycling efforts might be environmental theater—making us feel good without actually helping much. Washing and recycling a single-use plastic container that required extensive transportation might generate more carbon emissions than just making a new one. It's an uncomfortable truth, but pretending otherwise doesn't help anyone.

The Environmental Trade-Offs Nobody Talks About

Let's talk about something that doesn't make it into the glossy promotional materials: the environmental costs of recycling technology itself. Those AI-powered sorting robots? They require rare earth minerals for their electronics and consume electricity continuously. Chemical recycling facilities need enormous energy inputs. Landfill mining operations burn diesel fuel for excavators and generate dust and emissions.

This doesn't mean we shouldn't pursue these technologies—it means we need to be honest about the trade-offs. A recycling system powered by coal-fired electricity might not be as green as it appears. The carbon footprint of manufacturing and operating sophisticated recycling equipment needs to be factored into the equation. Sometimes the low-tech solution is actually more sustainable than the high-tech one.

What's Actually Coming Next

Despite the challenges, some genuinely exciting innovations are on the horizon. Smart waste management with IoT sensors is growing rapidly, with the market predicted to climb from $2.7 billion in 2024 to nearly $14 billion by 2035. Fill-level sensors in bins will optimize collection routes, reducing fuel consumption. Data analytics will help municipalities track waste patterns and improve efficiency.

Biological recycling is another frontier. Researchers are developing enzymes and bacteria that can break down plastics that resist conventional recycling. It sounds like science fiction, but enzyme-based systems are being developed that can retain 85% activity after 10 cycles, making continuous operation feasible. The costs are still high—$100-500 per kilogram of enzyme—but AI-driven evolution of these biological systems could bring significant improvements.

Modular electronics design is gaining traction too, driven by right-to-repair laws and consumer demand for sustainability. When devices are designed from the start to be taken apart and upgraded, recycling becomes dramatically easier. Instead of extracting tiny amounts of precious metals from sealed smartphones, we could swap out modules and recycle clean components. It's a shift in thinking from disposable to maintainable.

The Circular Economy Dream

All of this feeds into the broader vision of a circular economy—where materials flow in closed loops rather than following a linear path from extraction to disposal. The idea is beautiful: design products for disassembly and reuse, minimize waste generation, recover maximum value from materials at end of life, and feed those materials back into new production.

The landfill mining market is projected to grow from $180.7 million in 2025 to $287.4 million by 2035, driven by urban land scarcity, circular economy policies, and technological advances. Countries are implementing zero-waste targets and extended producer responsibility frameworks. The momentum is real.

But making the circular economy work requires more than just technology—it requires systemic changes in how we design, manufacture, use, and dispose of products. It requires honest accounting of environmental and economic costs. It requires accepting that not everything can or should be recycled, and focusing our efforts where they'll make the biggest difference.

The Bottom Line

The future of recycling is genuinely exciting. We've come so far from throwing everything in one big dump, and the technologies emerging now could take us even further. AI sorting, chemical recycling, landfill mining, biological decomposition—these innovations have real potential to dramatically improve how we handle waste.

But we need to stay grounded in reality. Technology alone won't save us if the economics don't work or if the environmental costs outweigh the benefits. The goal shouldn't be to recycle everything at any cost—it should be to create sustainable systems that actually reduce our environmental footprint in meaningful ways.

So yes, those massive landfills might eventually be mined for resources, but only where it makes economic and environmental sense. Yes, robots will get better at sorting our trash, but we still need to reduce how much trash we generate in the first place. Yes, chemical recycling might handle plastics we can't recycle today, but we should also question whether we need all that plastic packaging to begin with.

The future of recycling isn't just about better technology—it's about better decisions. And sometimes the greenest choice is the one that doesn't require any recycling at all.